This is custom heading element

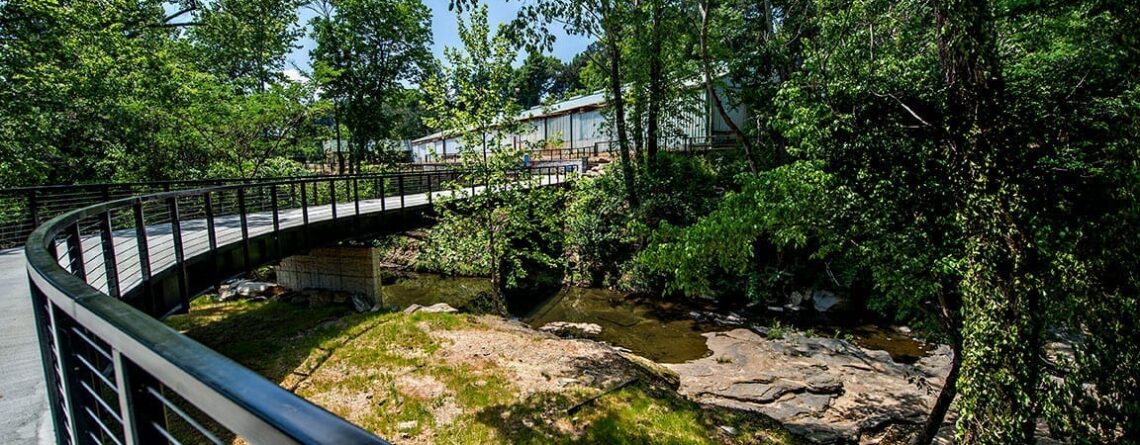

Illegal tire dumping. Land contaminated by toxic chemicals. Fetid standing water. Sewer overflows. These are just a few of the environmental health issues that for decades have plagued the Proctor Creek Watershed, a 16-square-mile swath of Northwest Atlanta that includes dozens of neighborhoods.

In 2013, Proctor Creek caught the attention of activists and researchers when the watershed was added to the Urban Waters Federal Partnership, an Environmental Protection Agency program meant to reconnect communities with their urban waterways. Finally, there was investment and momentum to tackle the pollution and neglect, but the community was skeptical about whether the publicly available data were comprehensive enough to reflect all of their concerns.

“It’s important to identify what’s actually impacting the people who live in the community,” says Na’Taki Osborne Jelks, co-chair of the Proctor Creek Stewardship Council and a recent Ph.D. graduate from Georgia State’s School of Public Health. “Yet datasets often miss that fine-grained, street-level data.”

To address the problem, Jelks and other Georgia State public health researchers began working to build an app that would allow watershed residents to identify and document the environmental hazards that were negatively affecting their health and quality of life. Jelks says that bringing in community members to co-design the mapping tool was key.

“We were able to leverage community expertise to determine which problems to focus on and how to formulate the queries in a way that was user-friendly,” she says.

With the app in hand, longtime residents teamed up with Georgia State faculty members and students to collect photo and video evidence of environmental hazards in their neighborhoods. The data were then used to generate a series of maps, which showed where illegal dumping, stormwater infrastructure problems and other issues were most densely clustered.

Since the research was published last year, the group has been asked to present its findings to Atlanta city councilmembers and the city’s Department of Watershed and Department of Public Works. The project has also helped empower residents of the Proctor Creek Watershed to advocate for meaningful change, says Christine Stauber, associate professor of environmental health at Georgia State and one of the study’s authors.

“One advantage of community-based participatory research is that it also creates a space for community members to be part of the solutions process,” she says. “And when the community becomes involved in conversations around policy, that in turn puts a human face on the problem.”

As a resident of Atlanta’s Westside for more than two decades, Jelks agrees.

“I saw for myself how residents can be marginalized when they bring their concerns to officials. Sometimes they’re seen as lacking credibility,” says Jelks, who is now an assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Spelman College. “We started to think about how the community can back up its claims in a way that’s rigorous enough to be respected by the people who can take that data and make it actionable.”

Photo by Jonathan Phillips

Leave a Reply