Years of collaboration and hard work lay the groundwork for the university's transformation into a leading research institution. Here, a look back at a few of the defining moments in Georgia State's research history.

Written by Jennifer Rainey Marquez

Illustrations by John Dykes

Written by Jennifer Rainey Marquez | Illustrations by John Dykes

OVER THE PAST FEW DECADES, GEORGIA STATE HAS BEEN AN INSTITUTION IN TRANSITION, evolving a small-scale research operation into a powerful engine of discovery. There wasn’t a single moment that sparked this dramatic transformation. Rather, years of collaboration and hard work by innovative faculty members, administrators and off-campus partners lay the groundwork for research success. In 1996, Georgia State was designated an R1 university, and since then we’ve earned a place among the nation’s top research institutions. Here’s a look at how we did it our way — THESTATEWAY®

2009

Tapping into the Power of Teamwork

Georgia State has long recognized that interdisciplinary research and collaboration are what’s needed to address the complex issues facing our society. In 2009, in advance of Georgia State’s centennial in 2013, the university began an ambitious initiative to recruit top faculty with shared, interdisciplinary research interests. The idea: To build collaborative teams of world-class scholars that could tackle grand challenges and take Georgia State to the next level as a research institution.

Known as the Second Century Initiative (2CI), the program was responsible for bringing 61 new faculty to Georgia State over the course of five years in areas as diverse as neuroimaging, astrophysics, adult literacy and the future of cities. To maintain the trajectory, the university introduced a successor to the 2CI program in 2016. The Next Generation program, which recruited 27 faculty over four years, continued interdisciplinary hiring in areas of core and emerging research strength. Today, those faculty are studying space weather events, using machine learning and big data analysis to investigate how the legal system operates and working to counter terrorism and violent extremism.

“Georgia State had officially earned the R1 designation, but we knew we needed bold action to put us in the same league as other major research institutions,” says Risa Palm, Georgia State’s former provost and senior vice president, who oversaw the program. “I think it has resulted in a more connected and more vibrant culture of research at the university.”

2010s

If You Build It…

Kell Hall, which Georgia State acquired in 1945, was the birthplace of science at the university. A former parking garage, it housed labs full of bubbling chemical reactions, subatomic machinery, even cadavers. But by the 2000s, Kell’s 180,000 square feet — plus the 170,000-square-foot Natural Science Center, which opened in 1992 — wasn’t enough to accommodate the university’s growing research portfolio. Georgia State began planning for a new research park that would be a hub for scientific discovery.

The opening of Petit Science Center (PSC) in 2010 and the Research Science Center (RSC) in 2016 more than doubled the university’s research space and marked a new era for research at the university. With vastly improved lab space and the most advanced core facilities, the buildings gave the university a major advantage in recruiting top faculty in the life sciences. Today, PSC and RSC serve as home for Georgia State’s Institute for Biomedical Sciences, the Neuroscience Institute, the Biology and Chemistry departments, and numerous research centers.

“These are the things that are really key to building a strong research enterprise: critical facilities and specialized cores with equipment that faculty want to use,” says Robin Morris, former vice president for research at Georgia State.

1993

Landing World-Class Scholars

For more than 30 years, the Georgia Research Alliance (GRA)’s Eminent Scholar program has worked to grow the state’s university research capacity by building up a bedrock of talent. In 1993, Georgia State joined the Eminent Scholar program with the recruitment of Ron Cummings, one of the nation’s top environmental economists, as the Noah Langdale Jr. Eminent Scholar in Environmental Policy. Cummings later became director of the Andrew Young School’s Environmental Policy Program.

For more than 30 years, the Georgia Research Alliance (GRA)’s Eminent Scholar program has worked to grow the state’s university research capacity by building up a bedrock of talent. In 1993, Georgia State joined the Eminent Scholar program with the recruitment of Ron Cummings, one of the nation’s top environmental economists, as the Noah Langdale Jr. Eminent Scholar in Environmental Policy. Cummings later became director of the Andrew Young School’s Environmental Policy Program.

“Ron brought with him a big-time academic reputation,” said the school’s then-dean Roy Bahl in a 2005 interview. “He developed our work on air pollution, water resources and solid waste disposal, and along the way was instrumental in developing a world-class laboratory in experimental economics. He made our environmental policy center a nationally known place.”

In the years since, Georgia State has hired 11 faculty through the Eminent Scholars program. Today, our eight scholars are producing major contributions in fields ranging from neuroscience to drug discovery to emerging infectious diseases. The university’s newest Eminent Scholar, Vince Calhoun, was recruited in 2019 and is the first to receive secondary academic appointments at two other GRA member institutions: the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University.

“Georgia State has been part of the Georgia Research Alliance since day one 30 years ago,” says Susan Shows, president of GRA. “At the time, it was a university of great potential in scientific exploration. We’ve seen that potential fulfilled in recent years.”

1980-1990s

It Takes a Village

The Language Research Center (LRC), which opened in 1981 about 10 miles southeast of Georgia State’s downtown Atlanta campus, was an outgrowth of what was then the university’s most famous research endeavor: the LANA project. Spearheaded by Duane Rumbaugh, a Regents’ Professor of Psychology who died in 2017, the project used a pioneering computer-based symbol system to allow a human and chimpanzee to communicate. Rumbaugh’s research was featured in Time magazine, the New York Times and “60 Minutes” and its most successful primate subjects became media stars. Subsequently the LRC played host to important figures — John Lewis, Paul McCartney and a slew of scientists — eager to learn more about the researchers’ innovative approach to language learning, an approach that continues today.

“At the time, there weren’t that many teams of researchers here that were doing such internationally recognized and federal grant competitive research,” says Morris, who came to the university in 1982 and worked with the LRC in its early years. “This was one of the first real research centers that attracted scientists from around the world and really made people pay attention to Georgia State.”

Nearly 20 years later, the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience (CBN) made headlines when it was established with a $37 million grant from the National Science Foundation, along with $16 million from the GRA. Initially headed by Tom Insel, then director of the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center at Emory University, CBN moved to Georgia State in 2002 under the direction of Regents’ Professor of Neuroscience Elliott Albers. The inter-institutional center brought in diverse faculty and fostered interdisciplinary scientific study — and lay the groundwork for the university to create its own hub for interdisciplinary neuroscience education and research: the Neuroscience Institute, which was founded in 2008.

“This was the biggest single grant ever to come to Georgia State, and it was really foundational at a time when Georgia State was starting to remake itself into a research powerhouse,” says Albers.

The LRC and CBN were among the first research centers to put Georgia State on the map. Today, there are more than 70 research centers and institutes housed in Georgia State’s schools and colleges. The institution is also home to six university-level research centers — including CBN —that bring together investigators from across disciplines to address critical quality of life issues. These research teams are working to develop new medicines and diagnostic tools, transforming our understanding of how mental illness unfolds in the brain and promoting greater well-being for children and families in Georgia and across the world.

1998

A “Game-Changing” Laboratory

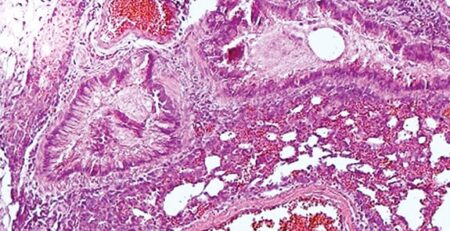

When it was built in 1998, Georgia State’s biosafety-level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory was the first such facility in the nation on a university campus. In fact, the U.S. has only a handful of these tightly controlled labs, which are used to safely conduct research on infectious and emerging diseases.

A global resource funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Research Resources, the BSL-4 was established when Georgia State and the GRA recruited Julia Hilliard to the university as an Eminent Scholar. Hilliard studies the Herpes B virus and other zoonotic viruses passed from animals to humans.

“It put Georgia State out there in the scientific community and the Atlanta community to have something as unique as a BSL-4 laboratory,” says Mike Cassidy, a Georgia State alum who was then vice president of the GRA. “It was a game-changing moment for the university.”

The BSL-4 is part of the university’s high-containment core, a suite of secure research facilities where faculty are dedicated to the study of infectious diseases that threaten millions of lives each year. Using these specialized labs, Georgia State scientists can safely conduct sophisticated research on existing and emerging pathogens, including West Nile virus, Zika virus and SARS-CoV-2.

“Building a BSL-4 laboratory at Georgia State in the late 1990s and recruiting GRA Eminent Scholar Julia Hilliard to run it was an early vote of confidence in the university,” Shows says. “It’s still very significant to have a BSL-4 lab at a university, but at the time, it was unheard of. That was an early development that set Georgia State on a trajectory of increasingly important — and impressive —research.”

1990-2000s

New Schools, New Research Focus

During the 1990s and 2000s, the university grew rapidly, establishing three new schools and institutes: the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies (1996), the School of Public Health (2013) and the Institute for Biomedical Sciences (2014). All were imbued with a strong research focus from the beginning.

Since its founding 25 years ago, the Andrew Young School has brought together researchers from across disciplines to address complex policy and public management issues. The school is home to nearly a dozen research centers, including the Georgia Health Policy Center, which aims to boost health at the community level; the Georgia Policy Labs, which leverages data to better the lives of children and families; and the Evidence-Based Cybersecurity Research Group, which reviews cybersecurity policy and develops tools to prevent cyber-crime. The school is also well known for its work in public finance and experimental economics — its Experimental Economics Center, where researchers are aiding in the development of new data-supported economic theory, is the only one of its kind in the Southeast.

In the School of Public Health, two major grants helped kickstart the research program early on. Even before its official designation as a school, the then-Institute of Public Health received $6.7 million in 2010 to create a Center of Excellence on Health Disparities Research. The grant, which came from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), funded a five-year study of health disparities among minority populations in metropolitan Atlanta. In 2013, the school was awarded $19 million from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the NIH to establish one of 14 Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science. The center’s researchers, led by Michael Eriksen, Regents’ Professor and the school’s founding dean, were focused on understanding human decision-making around the use of tobacco.

“A world-class public health school must have a robust externally funded research program that makes a difference in people’s lives,” says Eriksen. “I’m proud to say that the Georgia State School of Public Health far exceeds this expectation.”

In 2011, Georgia State created its first university-level research center — the Center for Inflammation, Immunity & Infection, dedicated to the study of inflammatory diseases and the development of novel therapeutic strategies — led by GRA Eminent Scholar Jian-Dong Li. Three years later, the center was absorbed into a new institute, led by Li and created with the purpose of advancing Georgia State’s translational biomedical research.

Since then, the Institute for Biomedical Sciences has evolved to offer three degrees and house four research centers focused on life-threatening infectious diseases. The newest — the Center for Translational Antiviral Research — was established earlier this summer to fill the gap for developing affordable, much-needed antiviral drugs that will meet the threats posed by existing and evolving viruses.

2000

Making a Splash in the Sky

High above Los Angeles, the Mount Wilson Observatory is home to some of astronomy’s most historically important instruments, including the 100-inch Hooker telescope, which allowed Edwin Hubble to prove the universe is expanding, and a 20-foot stellar interferometer that was used to measure the diameter of a star for the first time. In the 1980s, Georgia State began planning its unique instrument at Mount Wilson, the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy — or CHARA — Array.

High above Los Angeles, the Mount Wilson Observatory is home to some of astronomy’s most historically important instruments, including the 100-inch Hooker telescope, which allowed Edwin Hubble to prove the universe is expanding, and a 20-foot stellar interferometer that was used to measure the diameter of a star for the first time. In the 1980s, Georgia State began planning its unique instrument at Mount Wilson, the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy — or CHARA — Array.

“I came to Georgia State in 1977 and began studying binary stars using a new technique called speckle interferometry that had just been invented,” says Regents’ Professor Emeritus Hal McAlister, CHARA’s founder and first director. “At the time, the largest telescope available was four meters in diameter.”

CHARA uses a process known as optical interferometry, which incorporates signals from multiple telescopes to create a high-resolution image. Six telescopes spread across the mountain combine to simulate a single 300-meter instrument — making CHARA the world’s most powerful optical interferometer.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) provided funding for preliminary engineering studies and construction. After 15 years of planning, the array was officially dedicated in October 2000. In 2002, the Cleon C. Arrington Remote Operations Center was established, allowing researchers to control the facility from anywhere in the world. It was named for Arrington, the university’s vice president of research from 1984 to 1999, in honor of his unwavering support of CHARA.

“I don’t think that this could have happened anywhere but at Georgia State at the time that it occurred,” says McAlister. “This was a moonshot idea — probably the largest possible project that a small group like ours could have taken on — but we believed in it, and so did the university administration.”

Since receiving its first NSF grant in 1985, CHARA has brought in $32 million in federal funding, along with $2.1 million from private foundations. In 2016, scientists at CHARA received nearly $4 million from the NSF to provide scientists around the world with greater access to the instrument, a program that is now being expanded with another $4.8 million grant.

“Because the CHARA Array is such an important resource for the global research community, demand for time has been high,” says Theo ten Brummelaar, director of the array. “The NSF grant will allow us to go from 60 nights of observing time per year to 100 nights per year.”

Another new $2.5 million grant will fund the addition of a seventh mobile telescope, expanding the array’s power to produce images on many different size scales.

“Our telescopes are currently separated by up to 330 meters, but that’s still not far enough apart to see, for example, the surfaces of stars in fine detail. On the other end of things, it’s a challenge for us to get good images of some stars because they’re too large,” says Doug Gies, Regents’ Professor of Physics and Astronomy and director of the center. “With the mobile telescope, we can push the limits on both ends.”

Leave a Reply