This is custom heading element

[post-fields post_field=”wpcf-subtitle”]

[post-fields post_field=”wpcf-byline”]

Cerebral palsy (CP), which can result from abnormal brain development or a brain injury in utero or shortly after birth, is the most common childhood physical disability, affecting approximately 1 in 345 kids. Physical therapy can help improve children’s motor skills and prevent the disability from worsening over time, but not all kids with CP have equal access to in-person therapy, says Yuping Chen, associate professor of physical therapy in the Byrdine F. Lewis College of Nursing and Health Professions.

Even for kids who participate in therapy, “parents have to take the time to supervise their progress,” she says. “And it can be boring for kids to practice at home on their own.”

To help keep kids motivated and expand access to therapy, she and her collaborators have turned to technology. They’re working to test and develop virtual reality games — even a humanoid robot — as at-home intervention tools for pediatric patients.

For World Cerebral Palsy Day, we spoke with Chen about her research and how technology can help give kids with CP a better life.

Why did you decide to focus on this patient population?

While I was studying physical therapy as an undergraduate student, one of my professors was a pediatric therapist. One day she brought in some children with cerebral palsy and demonstrated skills to facilitate their movements. It was an eye-opening experience. I’m an only child, but I loved being around young children. I knew I wanted to work with babies and kids, and one of the most common populations in pediatrics is children with cerebral palsy.

Why is physical therapy so important for kids with CP?

By helping kids better control their movements, we can unleash their potential. Because CP is related to brain injury, people often assume that children also have intellectual disabilities. It’s a misconception that gets reinforced because motor disabilities can sometimes interfere with children’s ability to communicate, which makes it tough for them to show what they’re capable of. When a child gets labeled as someone who can’t participate in activities, it limits them.

What role can technology play in helping kids with CP achieve their potential?

As researchers, we’re constantly asking whether we can become effective or more efficient at helping our patients improve their motor skills. A few years ago, I was starting to use virtual reality (VR) in my case studies, because it makes the therapy more fun for kids and helps keep up their stamina.

When I would ask parents to bring their children with CP to our lab after school, though, they’d inevitably respond, “Can you come to my house instead?” Because nobody wants to drive to downtown Atlanta during rush hour. That gave me the idea to develop a way for kids to use virtual reality at home. It’s portable, it’s convenient, and it can help expand the number of people who have access.

Around the same time, someone introduced me to Ayanna Howard, a brilliant roboticist who was then a faculty member in the College of Computing at Georgia Tech. It’s a dream come true to work with her, because I know technology can help kids and she can build the platforms that allow us to achieve our goals.

How does the VR platform work?

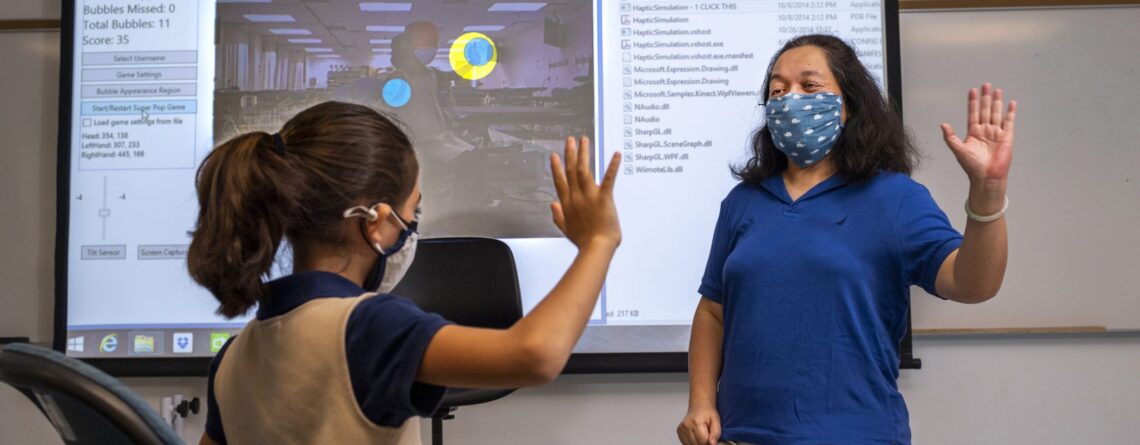

The kids think they are playing a game, but actually they’re being evaluated and then encouraged to participate in exercises that will help them improve. The game involves making reaching movements — the kids work to “pop” virtual bubbles — and the computer measures their range of motion.

We don’t use immersive VR because kids can get motion sick. Instead, there’s a camera that allows them to see themselves and the bubbles on a screen; when they move their arm, the arm moves in the game at the same time. We adapted the algorithm so the camera could differentiate between a child and their wheelchair, and we configured it so that the child doesn’t need to hold anything. Kids with CP sometimes have trouble grasping, but even a child with severe CP can still play the game. In fact, one of the first few study participants was a child who has a very severe type of CP, and it was the first time he could play a video game just like his siblings. You should have seen his smile.

The game is very adaptable and we can change the range for people with different abilities. For example, we can make the bubble bigger and closer or smaller and further away. We also started to incorporate other types of movements, like holding on to a bubble or dragging another bubble over towards it.

Tell us more about the humanoid robot. How did that work come about?

We’ve heard through home-based interventions that caregivers don’t always have time to engage their kids in therapy as much as they should. But we’re talking about children, so they need an adult to supervise them. We thought about whether we could use a humanoid robot developed by Dr. Howard as the “supervisor,” telling the kids what to do and providing feedback.

We have an ongoing a study comparing the feedback from the robot versus a human therapist. Generally, we aren’t seeing a big difference. But we’re also finding that participants still prefer humans. Therapists won’t be replaced by robots, but there are instances where therapists’ work could be augmented by this technology.

What’s next for your research?

We hope this technology could be integrated into telehealth to close gaps in access to healthcare for high-needs kids. We want to help people who live in rural areas. In southeast Georgia, interventionists have to cover something like 13 counties. That’s not sustainable.

For the VR game, the next step is to make it more user-friendly and easier to navigate. For the robot, it’s about making it more affordable. Almost every robot we’re using that can provide feedback is relatively expensive and not accessible for most families. If our study shows that the robot can provide effective feedback, then the engineering team will work to design a robot that’s more affordable. The piece I’m working on is fine-tuning the feedback: determining the best type of feedback, the best frequency. There are still questions we need to answer; for example, should we only provide feedback when they do something correctly or when they do something wrong?

We’re motivated because children with CP deserve a better life, and we believe we can use technology to help them participate in the same kinds of activities as other kids.

Portraits by Carolyn Richardson

Leave a Reply