This is custom heading element

D

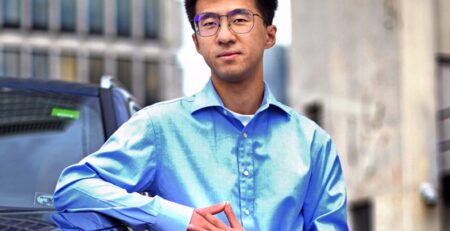

uring puberty, a boy’s vocal folds elongate, causing his voice to deepen, sometimes by an octave or more. As boys mature through these changes, it may become more difficult for them to control their voices. Historically, male singers were sidelined during this time, sometimes kicked out of choirs or told to stop singing until they were adults. Music education professor Patrick Freer knows this firsthand.

“I was a boy who was told my voice was ‘broken’ when it started to change,” he says. “It took years for me to make my way back to singing. It wasn’t until college that I found a teacher who said, ‘Well, let’s see what you can do instead of what you can’t do.’”

For decades, Freer has focused his research on how choral teachers can more effectively guide boys whose voices are starting to change. His work earned him an invitation to spend the fall 2018 semester working with faculty at the Universität Mozarteum Salzburg, one of Europe’s leading music conservatories. While there he became involved in a project with the Vienna Boys Choir, which was established more than five centuries ago and is one of the best-known boys’ choirs in the world.

Its conductor, Gerald Wirth, has made the group notable for their inclusion of boys with changing voices, Freer says.

“He has developed a system of working with adolescents that has become informally known as the Gerald Wirth method,” he says. “At first, the choir’s funders were simply interested in codifying his technique, but as more researchers got involved, it moved beyond that. Now we are focused on analyzing what makes his method and that of good choral teachers in general so successful?”

To do that, the choir’s leadership has brought together an interdisciplinary team of researchers. There are neuroscientists who are interested in studying how different choral instruction approaches affect the brain, as well as the resulting musicianship. There are computer scientists who are developing simulated classrooms to train educators and technology to analyze choral teaching techniques.

Freer and his colleague Helmut Schaumberger of the Mozarteum are working to inform those efforts by contributing their expertise in instructional methods and teacher training. In February, they began working on a review of the existing research into effective techniques of successful choral instructors and conductors.

“We do know that there are choral teachers who are more successful than others, but we haven’t necessarily done a good job of figuring out exactly why that is,” Freer says. “There’s an old adage in our field, which is ‘We had a great choir program in our school, and then she left.’ I hope this project might lead to a more evidence-based set of standards and methods and tools that can be applied in all different kinds of singing communities, not just those that include middle-school boys.”

Freer stresses that getting it right in adolescence is critical when it comes to music education. He has conducted numerous studies showing that if people, particularly boys, stop singing in adolescence they will likely never sing again.

“Many teachers will say that adolescent boys don’t like to sing,” says Freer. “Well, that’s not what I find in my research. Boys do like to sing. It’s choir — the method or format of the instruction — that’s the problem. So now the question is, what do we do about that?”

Photo by Meg Buscema

Leave a Reply