written by Ann Hardie

written by Ann Hardie

unrelenting

howling.

unrelenting

howling.

The

unrelenting

howling.

That is what Ann-Margaret Esnard remembers most from nearly 40 years ago when Hurricane Allen tore through the small Caribbean Island of St. Lucia, where she grew up. Esnard rode out the Category 4 storm under a table in her family’s living room.

“That sound,” she says, “was the most terrifying thing.”

The 1980 hurricane pummeled the Caribbean and parts of the East Coast and is credited with more than 200 deaths. As a young person, Esnard had seen other vicious storms, but she says Allen was the one that awakened her to the potentially devastating impacts of hurricanes.

“You go outside and see downed trees and power lines and houses with rooftops blown off and windows blown out,” she says. “You wonder if your island is ever going to recover.”

Four decades later, Esnard, the interim associate dean for research at the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, has spent most of her academic career studying how communities can minimize the impact of disasters and bounce back if they do get hit. Her research has delved into the circumstances that make areas vulnerable to storms, the role that housing and land development play in the recovery process and the factors that cause people to be displaced from their homes for long periods of time.

Esnard’s work could not be more critical given the increasing number of weather-related disasters.

“Last year was an exceptional year, with one disaster after another after another,” she says, citing the hurricanes that affected Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, and the wildfires and mudslides in California.

In 2013, Georgia State recruited Esnard, a Distinguished University Professor in the Department of Public Management and Policy, as part of the university’s Second Century Initiative to encourage interdisciplinary, collaborative research.

“Esnard’s work on these complex problems exemplifies the agenda that Georgia State has undertaken as part of the Second Century Initiative,” says Provost Risa Palm. “Her work will make cities such as Atlanta stronger and even more resilient places.”

While Atlanta isn’t prone to severe natural disasters given its inland location, the city’s robust economy and accessibility could make it a likely landing place for people uprooted by future disasters.

“We are absolutely a potential destination for evacuees,” Esnard says. “And given Atlanta’s existing challenges with traffic congestion, aging infrastructure and housing affordability, that is something we have to plan for.”

“We can’t prevent natural disasters. The question is, how do we minimize the loss of lives, God forbid, and the loss of property?”

“We can’t prevent natural disasters. The question is, how do we minimize the loss of lives, God forbid, and the loss of property?”

Growing up in the Caribbean, Esnard experienced hurricanes as something to be feared and avoided, not studied and obsessed over.

“Disasters were a bad experience that I stored somewhere in the back of my brain,” she says. “I never thought that my journey would one day take me to a point where disaster is an ever-present thought.”

Although her home of St. Lucia is known for its laid-back culture, Esnard was educated in schools that followed a strict British model, where students were ranked according to their grade point averages. She flourished under the pressure.

“It was tough love. I always wanted to make sure I was in the top,” says Esnard, who describes herself as “competitive,” “highly motivated” and “highly organized.”

After a short stint as a high school teacher, Esnard left St. Lucia in 1987 to attend the University of the West Indies in Trinidad, where she earned a bachelor of science degree in agricultural engineering. She followed that with a master of science degree in agronomy and soils from the University of Puerto Rico in Mayagüez.

“I always assumed I would stay in the Caribbean,” she says. “I thought I would be out there in the fields, helping to make sure that we had good crop yields using appropriate irrigation systems.” It was the subject of her undergraduate thesis.

That assumption fell apart when Joseph Esnard, her high-school sweetheart whom she married in 1990, was accepted as a doctoral student in plant pathology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“I quickly realized that I needed to get back to studying,” she says. (Today, Joseph develops algorithms for automated systems, and the couple has two sons: Josh, an entrepreneur whose hair- and beard-shaping patented tool, The Cut Buddy, was featured on the reality TV competition “Shark Tank”; and Kriston, a ninth grader at Decatur High School.)

“We can’t prevent natural disasters. The question is, how do we minimize the loss of lives, God forbid, and the loss of property?”

While at UMass, Esnard decided to pursue a doctorate in regional planning, deepening her expertise in geospatial analysis and geographic information systems (GIS).

“I love that you can combine data in certain ways to inform planning and decision-making,” she says.

It was during a postdoctoral program at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill in 1995 that Esnard began to think about how to apply geospatial analysis to disaster planning. She had gone to Chapel Hill to hunker down and publish articles based on her dissertation, which focused on using GIS technology for planning education. But Esnard is a collaborator by nature, and it did not take long for her to start hunting for another joint project.

She began working with David Brower, a UNC professor and one of the country’s foremost experts on coastal zone management, helping him develop a hazard mitigation plan for the town of Nags Head on the Outer Banks, a strand of barrier islands along the east coast of North Carolina that is constantly battered by storms from the Atlantic Ocean. For the project, Esnard used GIS technology to analyze land use, critical infrastructure and other data to assess the property and infrastructure at risk from hurricanes, storm surges and flooding. That information was later used by public officials and the private sector to shape policies on land development and housing.

“This experience really did flick a switch for me — that you could use this kind of analysis in disaster planning,” Esnard says. “We can’t prevent natural disasters. The question is, how do we minimize the loss of lives, God forbid, and the loss of property?”

“There will be future disasters. Climate change is real. There is so much to study. There is so much to plan for.”

“There will be future disasters. Climate change is real. There is so much to study. There is so much to plan for.”

“There will be future disasters. Climate change is real. There is so much to study. There is so much to plan for.”

On Aug. 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina tore into the Gulf Coast at 170 miles per hour, decimating coastal Mississippi and Louisiana. The storm itself exacted tremendous damage, but its aftermath — more than 50 breached levees and floodwalls, the highest-ever recorded storm surge — was catastrophic. More than 1,800 people died, and damage was estimated at $125 billion. (In 2017, Hurricane Harvey — which hit Houston particularly hard — tied Katrina as the costliest storm on record, although the death toll was much lower, with 108 confirmed deaths.)

“Hurricane Katrina changed everything,” says Esnard, who delineates her academic career as pre- and postKatrina. “After that storm, it became painfully obvious that we had to think about ‘long-term’ and ‘recovery’ in a more nuanced way.”

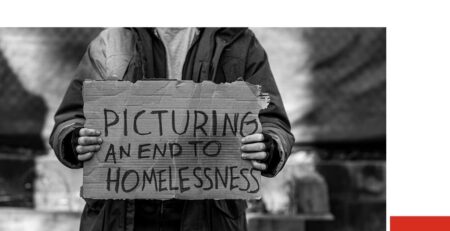

Post-Katrina, planners also had to grapple with issues involving the large numbers of people displaced from their homes — sometimes permanently.

“We had not really talked about long-term displacement before. Now people were scattered in Texas, in Alaska, all over the country,” Esnard says. “Some got on planes with only the clothes on their back. Those images are still burned into my mind. It’s thirteen years later, and parts of the Gulf Coast have not fully recovered.”

When the hurricane struck, Esnard had just begun teaching at the Florida Atlantic University campus in Fort Lauderdale, where some Katrina-affected families relocated. Esnard and a university-based team of urban planners and public administration faculty received a National Science Foundation grant to study long-term displacement after the storm.

“We needed to better understand whether people would be able to return quickly or would leave their homes and not come back at all,’” Esnard says. Their research led to the development of a tool, the Index of Relative Displacement Risk to Hurricanes, that is being revisited after last year’s hurricane season.

“We were the first group to develop this tool where you could look at a map and find out, ‘Wow, this area has a high risk of displacement or this area has a low risk,’” she says.

Esnard and her team identified several factors that affect displacement: social networks (the more support, the more likely people are to return), homeownership (renters are less likely to go back) and area of employment (those who work in the tourist industry may not have jobs to go back to in coastal cities).

Esnard has a keen interest in the recovery efforts in Puerto Rico, which was hit with a one-two punch from hurricanes Irma and Maria in September 2017. As the American territory struggles to restore even basic services, more than 200,000 Puerto Ricans have sought refuge in Florida and elsewhere.

“For the receiving communities, there are all kinds of issues to consider,” Esnard says. “How do you provide adequate housing, job opportunities and resources at schools for traumatized children?”

Esnard is collaborating with colleagues in the School of

Public Health to examine how schools recover after a disaster.

Esnard is collaborating with colleagues in the School of Public Health to examine how schools recover after a disaster.

At the core of strong cities are strong schools. Esnard and colleagues from the School of Public Health are in the middle of a research project to help schools recover more quickly following a disaster. The implications of their work, which is being funded by the National Science Foundation, extend far beyond the classroom.

“How fast communities get back on their feet depends on how fast schools get back on theirs,” Esnard says. “If schools are closed for long periods of time, children’s educational attainment and job prospects dim, which makes communities — particularly those facing repeated disasters — less resilient over time.”

Esnard is co-leading the project with Betty S. Lai, an assistant professor in the School of Public Health and an expert on post-traumatic stress in children who have experienced large-scale natural disasters. Lai calls Esnard the perfect partner.

“I’m a child psychologist with a background in statistics who is very focused on individuals,” Lai says. “We know that after disasters, children are at risk for developing mental and physical health problems. Yet we can’t really understand individuals without an understanding of the larger community, which is where Ann-Margaret — and her focus on infrastructure and community resources — comes in.”

Esnard credits the collaboration with better educating her on the human-scale impact of disasters.

“Working with Betty,” she says, “my research has become more informed by an understanding of the dilemmas that children and families face.”

Their research team is analyzing eight years of data on 465 Texas schools impacted by Hurricane Ike, which occurred in 2008. They are looking at a wealth of information — including academic performance, attendance and the length of a school’s closure — trying to discern why some of the affected schools have thrived while others haven’t.

The researchers aren’t far enough along to provide answers, but by focusing on data common to most schools, they believe their final recommendations will be on point for institutions no matter where they are located, whether the Gulf Coast or St. Lucia or Atlanta.

“It’s clear: There will be future disasters. Climate change is real,” Esnard says. “There is so much to study. There is so much to plan for.”

Leave a Reply