the FOOTSTEPS

of FREEDOM

Georgia State’s World Heritage Initiative is working to create global recognition for significant sites associated with the Civil Rights Movement. By nominating places such as Little Rock Central High School and the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park for permanent designation on the prestigious World Heritage List, the scholars will elevate the sites of the American freedom struggle to the same international level as the historic center of Rome and Stonehenge.

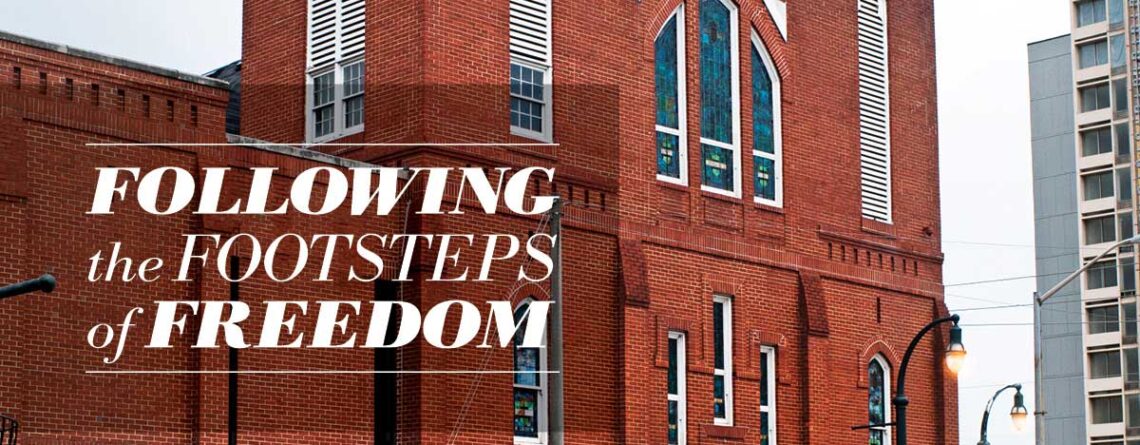

▲ The Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park • Atlanta

Encompassing the civil rights leader’s birth home, the church where he was pastor — Ebenezer Baptist Church — and his grave site, the 70-acre park is also home to the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change and the Sweet Auburn Historic District.

Photo by Steven Thackston

the FOOTSTEPS

of FREEDOM

Georgia State’s World Heritage Initiative is working to create global recognition for significant sites associated with the Civil Rights Movement. By nominating places such as Little Rock Central High School and the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park for permanent designation on the prestigious World Heritage List, the scholars will elevate the sites of the American freedom struggle to the same international level as the historic center of Rome and Stonehenge.

▲ The Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park • Atlanta

Encompassing the civil rights leader’s birth home, the church where he was pastor — Ebenezer Baptist Church — and his grave site, the 70-acre park is also home to the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change and the Sweet Auburn Historic District.

Photo by Steven Thackston

▲ The Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park • Atlanta

Encompassing the civil rights leader’s birth home, the church where he was pastor — Ebenezer Baptist Church — and his grave site, the 70-acre park is also home to the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change and the Sweet Auburn Historic District.

Photo by Steven Thackston

▼ Mourners fill Auburn Avenue on April 9, 1968, during the funeral service for Martin Luther King Jr. at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Photo courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

▲ Mourners fill Auburn Avenue on April 9, 1968, during the funeral service for Martin Luther King Jr. at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Photo courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

written by Charles McNair *

written by Charles McNair *

THE SWIRL OF EVENTS surrounding the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April grew deeply personal for a team of Georgia State University faculty.

After a King Center symposium, MLK50Forward, Glenn Eskew studied the waters spilling down a symbolic sculpture at King’s gravesite. Anne Farrisee paraded with the March for Humanity from Ebenezer Baptist Church to the Georgia Capitol. From the Auburn Avenue Research Library, Akinyele Umoja organized a livestream broadcast and discussion on King’s assassination.

Fifty years after a shot rang out in Memphis and hundreds of thousands of mourners filled the streets of Atlanta for a funeral, King’s dream for freedom and equality needs champions and icons more than ever.

“The story of the South is sometimes a horrific story about white supremacy, but it’s also a heroic story of great success,” says Eskew, professor of history and the project director of the World Heritage Initiative. “To see justice win out, to embrace nonviolence to do what’s right … it’s one of the 20th century’s most fascinating stories.”

Eskew and his partners want the whole world to remember that narrative, and he’s leading a herculean effort to make sure that happens.

The World Heritage Initiative project aims to nominate historic sites that were important to the Civil Rights Movement for permanent designation on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage List.

If successful, the initiative would elevate landmarks of the American freedom struggle — places like Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., and Central High School in Little Rock, Ark. — to the same international status as the Great Wall of China, Stonehenge and the Grand Canyon. The global community deems these sites as essential to humankind — places of inspiration for the world to cherish, respect and share.

“Inscription on the World Heritage List is a first step toward safeguarding these sites for future generations,” Eskew says. “It affirms their universal significance.”

Eskew partners in this ambitious work with Farrisee, the project manager, and Umoja, chair of the Department of African-American Studies, plus Richard Laub, emeritus director of the heritage preservation master’s degree program. A number of other Georgia State faculty advisers and graduate research assistants throw in their earnest energy, too.

The team also taps the expertise of an additional 100 preservationists, scholars, historic property owners and other stakeholders to support its visionary effort.

“We’ve evaluated more than 160 sites for this project,” says Eskew, “and we’ll list maybe a dozen of those for possible designation.

“The places we select must all work together in a holistic way. They have to fit together like pieces of a puzzle to tell the story of the freedom struggle.”

Georgia State’s World Heritage Initiative is working to create global recognition for significant sites associated with the Civil Rights Movement. By nominating places such as Little Rock Central High School and the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park for permanent designation on the prestigious World Heritage List, the scholars will elevate the sites of the American freedom struggle to the same international level as the historic center of Rome and Stonehenge.

THE SWIRL OF EVENTS surrounding the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April grew deeply personal for a team of Georgia State University faculty.

After a King Center symposium, MLK50Forward, Glenn Eskew studied the waters spilling down a symbolic sculpture at King’s gravesite. Anne Farrisee paraded with the March for Humanity from Ebenezer Baptist Church to the Georgia Capitol. From the Auburn Avenue Research Library, Akinyele Umoja organized a livestream broadcast and discussion on King’s assassination.

Fifty years after a shot rang out in Memphis and hundreds of thousands of mourners filled the streets of Atlanta for a funeral, King’s dream for freedom and equality needs champions and icons more than ever.

“The story of the South is sometimes a horrific story about white supremacy, but it’s also a heroic story of great success,” says Eskew, professor of history and the project director of the World Heritage Initiative. “To see justice win out, to embrace nonviolence to do what’s right … it’s one of the 20th century’s most fascinating stories.”

Eskew and his partners want the whole world to remember that narrative, and he’s leading a herculean effort to make sure that happens.

The World Heritage Initiative project aims to nominate historic sites that were important to the Civil Rights Movement for permanent designation on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage List.

If successful, the initiative would elevate landmarks of the American freedom struggle — places like Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., and Central High School in Little Rock, Ark. — to the same international status as the Great Wall of China, Stonehenge and the Grand Canyon. The global community deems these sites as essential to humankind — places of inspiration for the world to cherish, respect and share.

“Inscription on the World Heritage List is a first step toward safeguarding these sites for future generations,” Eskew says. “It affirms their universal significance.”

Eskew partners in this ambitious work with Farrisee, the project manager, and Umoja, chair of the Department of African-American Studies, plus Richard Laub, emeritus director of the heritage preservation master’s degree program. A number of other Georgia State faculty advisers and graduate research assistants throw in their earnest energy, too.

The team also taps the expertise of an additional 100 preservationists, scholars, historic property owners and other stakeholders to support its visionary effort.

“We’ve evaluated more than 160 sites for this project,” says Eskew, “and we’ll list maybe a dozen of those for possible designation.

“The places we select must all work together in a holistic way. They have to fit together like pieces of a puzzle to tell the story of the freedom struggle.”

▲ Edmund Pettus Bridge National Historic Landmark • Selma, Ala.

The Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for Confederate brigadier general, former U.S. Senator and a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, was the site of one of the most violent moments of the Civil Rights era. On March 7, 1965 — a day that came to be known as “Bloody Sunday — more than 600 voting rights activists en route to the Alabama state capitol in Montgomery were met by local lawmen who beat and tear-gassed them, chasing them back across the bridge.

Photo by Steven Thackston

▼ Coretta Scott King, widow of Martin Luther King Jr., and Civil Rights leader John Lewis (center) cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1975, commemorating a decade since the brutal events of “Bloody Sunday.”

AP photo

▲ Edmund Pettus Bridge National Historic Landmark • Selma, Ala.

The Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for Confederate brigadier general, former U.S. Senator and a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, was the site of one of the most violent moments of the Civil Rights era. On March 7, 1965 — a day that came to be known as “Bloody Sunday — more than 600 voting rights activists en route to the Alabama state capitol in Montgomery were met by local lawmen who beat and tear-gassed them, chasing them back across the bridge.

Photo by Steven Thackston

▲ Coretta Scott King, widow of Martin Luther King Jr., and Civil Rights leader John Lewis (center) cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1975, commemorating a decade since the brutal events of “Bloody Sunday.”

AP photo

ESKEW GREW UP IN BIRMINGHAM, dubbed “Bombingham” for the explosive violence leveled there last century at blacks seeking to end segregation. His life work has been an exploration of the roots and fruits of the freedom struggle. He grew up among the churches, parks and buildings that held the crucible of change that transformed our nation.

About a decade ago, he consulted with the State of Alabama to protect several churches that were vital to the movement. His connections with that work led to a significant grant in 2016 by the Alabama Department of Tourism for the World Heritage Initiative work at Georgia State.

With a deep bench of scholars and other experts, Eskew’s team looks into historic sites designated by the National Park Service, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and more. The initiative primarily limits its scope to the 1950s and 1960s, the decades most critical to the movement for justice.

The work of examining and evaluating scores of locations associated with the Civil Rights Movement is monumental, of course. And monumentally challenging.

In April 2017, the World Heritage Initiative team hosted a World Heritage and U.S. Civil Rights Sites Symposium at the Georgia State. More than 100 experts converged to share ideas and hear the goals of the initiative. Attendees there first learned of the designation of the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, rich with potential heritage sites, among other announcements.

Around the same time, Eskew, Farrisee and Laub drove through 13 states — 12,000 miles in all — making stops in dozens of towns to examine the first 80 or so properties.

It won’t be an easy, or fast, task. There are 1,073 places worldwide that have earned the World Heritage Sites designation. The United States has just 23 of them. Joining a list like this entails a lot of homework, planning and focus.

THERE’S A WORLD OF MEANING in the fact that Georgia State is leading an effort to establish new World Heritage Sites. It’s an appropriate role for a major university in Atlanta, says Umoja.

“This city is not only the birthplace of Dr. King, but also of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee,” he says of two more prominent players in the Civil Rights Movement. “Atlanta had a leadership role in the struggle for freedom, and now Georgia State has a leadership role in preserving that story.”

Anne Farrisee agrees.

“This brings the work of Georgia State to the world stage,” she says. “World Heritage designation is the highest possible recognition for places, and international visitors look for World Heritage Sites when they go to different countries. This would put the sites of the Civil Rights struggle on the same level as Machu Picchu or Bruges.”

Farrisee manages the exhaustive task of wrangling details such as organizing site visits and scholarly meetings, and keeping schedules and arranging other logistics for the team.

“The fact Georgia State was selected for this work means we have the right components in place to do large, complex, important projects,” Farrisee says. “It means our funders recognize our scholarship and think we’re a worthy investment.”

The project has also brought in a lot of funding and meaningful work for graduate students. One of those young researchers, Caitlin Mee, will step into the workforce later this year as a cultural resources manager.

“This project has really expanded my understanding of civil rights history,” Mee says. “My experience working with the team has been intrinsically valuable and will be in the future, too.”

ESKEW GREW UP IN BIRMINGHAM, dubbed “Bombingham” for the explosive violence leveled there last century at blacks seeking to end segregation. His life work has been an exploration of the roots and fruits of the freedom struggle. He grew up among the churches, parks and buildings that held the crucible of change that transformed our nation.

About a decade ago, he consulted with the State of Alabama to protect several churches that were vital to the movement. His connections with that work led to a significant grant in 2016 by the Alabama Department of Tourism for the World Heritage Initiative work at Georgia State.

With a deep bench of scholars and other experts, Eskew’s team looks into historic sites designated by the National Park Service, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and more. The initiative primarily limits its scope to the 1950s and 1960s, the decades most critical to the movement for justice.

The work of examining and evaluating scores of locations associated with the Civil Rights Movement is monumental, of course. And monumentally challenging.

In April 2017, the World Heritage Initiative team hosted a World Heritage and U.S. Civil Rights Sites Symposium at the Georgia State. More than 100 experts converged to share ideas and hear the goals of the initiative. Attendees there first learned of the designation of the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, rich with potential heritage sites, among other announcements.

Around the same time, Eskew, Farrisee and Laub drove through 13 states — 12,000 miles in all — making stops in dozens of towns to examine the first 80 or so properties.

It won’t be an easy, or fast, task. There are 1,073 places worldwide that have earned the World Heritage Sites designation. The United States has just 23 of them. Joining a list like this entails a lot of homework, planning and focus.

THERE’S A WORLD OF MEANING in the fact that Georgia State is leading an effort to establish new World Heritage Sites. It’s an appropriate role for a major university in Atlanta, says Umoja.

“This city is not only the birthplace of Dr. King, but also of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee,” he says of two more prominent players in the Civil Rights Movement. “Atlanta had a leadership role in the struggle for freedom, and now Georgia State has a leadership role in preserving that story.”

Anne Farrisee agrees.

“This brings the work of Georgia State to the world stage,” she says. “World Heritage designation is the highest possible recognition for places, and international visitors look for World Heritage Sites when they go to different countries. This would put the sites of the Civil Rights struggle on the same level as Machu Picchu or Bruges.”

Farrisee manages the exhaustive task of wrangling details such as organizing site visits and scholarly meetings, and keeping schedules and arranging other logistics for the team.

“The fact Georgia State was selected for this work means we have the right components in place to do large, complex, important projects,” Farrisee says. “It means our funders recognize our scholarship and think we’re a worthy investment.”

The project has also brought in a lot of funding and meaningful work for graduate students. One of those young researchers, Caitlin Mee, will step into the workforce later this year as a cultural resources manager.

“This project has really expanded my understanding of civil rights history,” Mee says. “My experience working with the team has been intrinsically valuable and will be in the future, too.”

▲ Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site • Little Rock, Ark.

The 1957 desegregation of the all-white Little Rock Central High School by nine African-American students was the flashpoint of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision that racial segregation in public education was unconstitutional.

Photo by Rett Peek

▼ The students, who became known as the Little Rock Nine, were initially denied entry by the Arkansas National Guard under the order of Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus. President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent troops of the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army to enforce the court order and escort the students into the school.

AP photo

▲ Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site • Little Rock, Ark.

The 1957 desegregation of the all-white Little Rock Central High School by nine African-American students was the flashpoint of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision that racial segregation in public education was unconstitutional.

Photo by Rett Peek

▲ The students, who became known as the Little Rock Nine, were initially denied entry by the Arkansas National Guard under the order of Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus. President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent troops of the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army to enforce the court order and escort the students into the school.

AP photo

WITH A LIFELONG CAREER IN PRESERVATION, Laub believes the World Heritage Initiative stands out.

“In the last two or three years, we’ve seen much more focus on the preservation of historic civil rights sites and their marketing to the public,” Laub says. “Until recently, mainly the African-American community was involved in preserving these places, but it’s now become a much more universal approach as awareness of the Civil Rights Movement grows.”

Eskew knows the bar is set high.

“It’s daunting, but it should be,” he says. “We’ll do our best to show why our nominations deserve the World Heritage Site designation.

“It seems very bureaucratic, but we’re talking about joining the most significant cultural, most unique places on earth,” he adds. “Our job is to argue the validity of about a dozen sites that, collectively, can be deemed worthy of outstanding universal value — the most important places in the world for the American freedom struggle.”

Farrisee felt the immensity of the project during the team’s whirlwind tour in 2017. Her epiphany came in a small town on the Mississippi Delta named Money.

“One of the sites was Bryant’s Grocery, where Emmitt Till, a black teenager, was lynched after he was accused of whistling at a white woman,” she says. “The store is now in ruins — no roof, most of the walls missing. It’s overrun with kudzu, and what’s left of Money stands around it, a tiny hamlet at the edge of the fields.

“I stood there and realized just how isolated that site was and how vulnerable African-Americans were in the Delta in those times. You can read about the event a hundred times but standing where it happened has such an emotional impact. It’s not a place that often made international headlines, but so much of the struggle happened there. You stand there, and you’re moved to tears.”

Bryant’s Grocery may not be one of the dozen or so Civil Rights Movement sites ultimately selected for World Heritage Site designation.

Still, nearly all of them, with their stories and stains, can move the world to tears.

RELATED CONTENT

WITH A LIFELONG CAREER IN PRESERVATION, Laub believes the World Heritage Initiative stands out.

“In the last two or three years, we’ve seen much more focus on the preservation of historic civil rights sites and their marketing to the public,” Laub says. “Until recently, mainly the African-American community was involved in preserving these places, but it’s now become a much more universal approach as awareness of the Civil Rights Movement grows.”

Eskew knows the bar is set high.

“It’s daunting, but it should be,” he says. “We’ll do our best to show why our nominations deserve the World Heritage Site designation.

“It seems very bureaucratic, but we’re talking about joining the most significant cultural, most unique places on earth,” he adds. “Our job is to argue the validity of about a dozen sites that, collectively, can be deemed worthy of outstanding universal value — the most important places in the world for the American freedom struggle.”

Farrisee felt the immensity of the project during the team’s whirlwind tour in 2017. Her epiphany came in a small town on the Mississippi Delta named Money.

“One of the sites was Bryant’s Grocery, where Emmitt Till, a black teenager, was lynched after he was accused of whistling at a white woman,” she says. “The store is now in ruins — no roof, most of the walls missing. It’s overrun with kudzu, and what’s left of Money stands around it, a tiny hamlet at the edge of the fields.

“I stood there and realized just how isolated that site was and how vulnerable African-Americans were in the Delta in those times. You can read about the event a hundred times but standing where it happened has such an emotional impact. It’s not a place that often made international headlines, but so much of the struggle happened there. You stand there, and you’re moved to tears.”

Bryant’s Grocery may not be one of the dozen or so Civil Rights Movement sites ultimately selected for World Heritage Site designation.

Still, nearly all of them, with their stories and stains, can move the world to tears.

* Charles McNair publishes nationally and internationally. The author of two novels, “Pickett’s Charge” and “Land O’ Goshen,” McNair was books editor at Paste Magazine between 2005 and 2015. He lives in Bogota, Colombia.

Leave a Reply